Generality

Hemochromatosis is a disease, generally on an inherited basis, characterized by the abnormal accumulation of iron in the body's tissues. If not diagnosed and treated in time, it can therefore cause serious damage to organs such as the liver, pancreas, heart, but also to the glands of the sexual sphere and joints.

Causes

The hereditary form, far more frequent, affects roughly one in three hundred individuals, with a certain prevalence in the male sex; the average age of onset is around 50 years.

As anticipated, while the normal individual normally absorbs 1-2 grams of iron a day, in patients with hemochromatosis this quantity increases to double or even triple; consequently, the iron deposits in the body also increase, from the standard 1-3 grams, to 20-30 or more grams.

Symptoms

To learn more: Hemochromatosis symptoms

The most characteristic symptom of hemochromatosis is the coloring of the skin, which acquires shades similar to bronze (once the disease was known as diabetes bronzino) and to slate gray, with chromatic alterations located mainly in the uncovered parts.

The symptomatology, in any case, is related to the amount of iron accumulations in the various tissues and includes: lethargy and fatigue, joint pain, loss of libido, abdominal pain, hypogonadism and increased volume of the liver (hepatomegaly), which can exceed 2kg.

It must be said, however, that the onset of these symptoms is extremely slow and progressive, so much so that the clinical onset normally occurs after 40 years and in an initially nuanced manner; often the onset of symptoms is anticipated by a fortuitous and casual diagnosis of hemochromatosis, for example during routine hematological tests.

Diagnosis

It is in fact possible to diagnose the disease through a simple blood test; in particular, those "spy" elements that reflect the extent of iron deposits in the body, such as ferritin and saturation of transferrin (sideremia), will be sought. A saturation of transferrin greater than 60% in men and 50% in women is a highly specific index of hemochromatosis in asymptomatic subjects

. The diagnostic confirmation can also be given by a small liver biopsy, which allows the evaluation of the organ's health at the same time, or from other tests, including genetic tests, which today are able to detect the small mutations implicated in the onset of the disease (with valence of screening). An important thing, in any case, is the extension of the test to the relatives, to verify in them an eventual iron overload; it is in fact known that the complications of hemochromatosis and the prognosis are all the more unfavorable the earlier the onset of the disease is and the diagnosis is delayed.

Complications

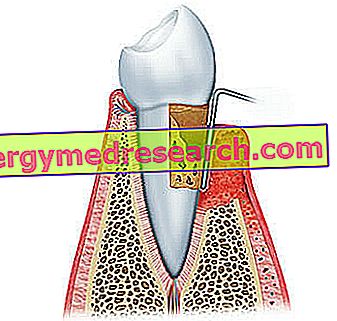

The organ that suffers most from iron accumulation is the liver, so that in the presence of hemochromatosis the risk of developing liver disease, such as cirrhosis, fibrosis and carcinomas, is significantly higher than in the normal population. Risk that increases even more in habitual drinkers, in those who follow a diet that is particularly rich in iron (the same red wine contains it in large quantities), after menopause (due to the cessation of menstrual losses) or in the presence of a viral hepatitis .

Concurrently, or more frequently afterwards, with cirrhosis, the patient may also develop diabetes mellitus, which reflects changes in the pancreas.

Care and treatment

To learn more: Drugs for the treatment of hemochromatosis

The treatment of hemochromatosis is aimed at the removal of excess iron before this leads to irreversible organ damage, with particular attention to hepatic complications (fibrosis and cirrhosis); in this regard the practice of periodic bleeding (phlebotomy) remains the cornerstone of therapy. Every 500 ml of blood removed, in fact, 250 mg of elemental iron are eliminated, at the same time stimulating the bone marrow to recall similar amounts of the mineral from the deposits (necessary for erythropoiesis, ie for the synthesis of new red blood cells). The frequency of bleeding, which is higher in principle (1-2 weekly withdrawals), then undergoes a rarefaction (3-4 per year), which however allows to prevent the re-accumulation of iron.

For patients with hemochromatosis there is also the possibility of undertaking chelation therapy, by taking drugs (the most famous is desferrioxamine) capable of complexing iron and facilitating urinary elimination; their effectiveness in promoting iron mobilization from deposits is less than bleeding, but they are one of the few useful alternatives in the presence of anemia (which represents a clear contraindication to phlebotomy). In the presence of hemochromatosis, the dietary approach involves a drastic reduction of foods rich in iron (red meat, offal, shellfish) and abstention from alcohol (important prohibition to prevent or slow the evolution of liver damage); at the same time the intake of whole foods and vegetables will be encouraged, which - thanks to the high fiber and phytate content - reduce intestinal iron absorption.