Types of Anemia

Anemias are classified according to alterations in the morphology of erythrocytes (red blood cells) and erythrocyte indices.

Whatever the nature of anemia, the reduction in the erythrocyte mass and oxygen carrying capacity, if sufficiently severe, leads to some very specific clinical characteristics.

Anemia can therefore be defined as a reduction of the oxygen transport capacity of the blood to the tissues. Since, in most cases, all this results from the reduction of red blood cells, anemia can be defined as the reduction below the normal limits of the mass of circulating red blood cells. However, this value is not easily measurable, therefore anemia is defined as the reduction, below the norm, of the volume of sedimented red blood cells, as measured by the hematocrit, or as a decrease in the hemoglobin blood concentration. Not to be underestimated is the fact that a fluid retention can expand the plasma volume while a loss can contract it, creating false anomalies of the clinically measured values.

Insights on the Common Forms of Anemia

Iron deficiency anemia Anemia and sport Pernicious anemia Sickle cell anemia Hemolytic anemia Folate deficiency anemia Pregnancy Anemia Aplastic anemiaSymptoms

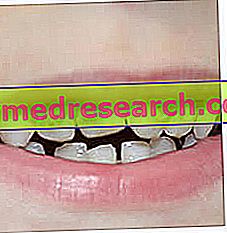

In the presence of significant anemia, patients appear pale. Common symptoms are represented by weakness, malaise and easy fatigue. The decrease in the oxygen content of the circulating blood causes dyspnea (air hunger) even for small efforts. The nails can become brittle and lose the normal convexity to take a concave, spoon-like shape ( coilonichia ).

Anoxia (lack of oxygen) can cause fatty degeneration in the liver, heart and kidney, characterized by the accumulation of substantial amounts of lipids in the cells of these organs, and by loss of the function of the occupied cells themselves.

If fatty degeneration in the myocardium (heart) is sufficiently severe, heart failure may occur, which is associated with respiratory difficulties due to reduced oxygen transport. In the acute loss of blood, as in the case of an important hemorrhage and established in a short time, can appear renal alterations characterized by oliguria (reduction of the production of urine) and anuria (absence of the production of urine) and due to the kidney no longer nourished by a normal blood supply (hypoperfuso). The hypoxia of the central nervous system can be evident with headache, decreased vision and fainting episodes.

Blood loss anemias

Blood losses can be acute, when they occur in a short time (minutes-hours), or chronic, when they occur more slowly, over months or years.

Clinical reactions to acute blood loss vary depending on the speed with which the bleeding occurs and whether it is external or internal. The alterations that develop during acute blood loss mainly reflect the decrease in blood volume rather than the loss of hemoglobin. The consequences can be a state of shock and death. If the patient survives, blood volume is rapidly restored by moving water from the interstitial fluid compartment. The resulting hemodilution (dilution of the blood) lowers the hematocrit levels. Reduced tissue oxygenation triggers the production of erythropoietin, to which the marrow responds by increasing erythropoiesis. When blood loss is internal, such as in the abdominal cavity, iron can be recovered. If, on the other hand, the loss is external, adequate reconstitution of the erythrocyte mass can be hindered by iron deficiency, if the reserves are insufficient.

Immediately after acute bleeding, red blood cells appear normal in size and color, ie normocytic and normochromic. However, when regeneration begins in the marrow, changes appear in the peripheral blood. The most characteristic is represented by the increase in reticulocytes, which reach 10-15% after 7 days.

Chronic bleeding involves anemia only when the lost altitude exceeds the regenerative capacity of erythroid precursors or when iron reserves are depleted. In addition to chronic hemorrhage, any cause of martial (iron) deficiency can lead to an identical anemic manifestation. Among these causes we find the states of malnutrition and intestinal iron malabsorption and an increase in demand above the daily intake, such as during menstruation or during pregnancy.