Generality

The vulvitis is an inflammation of the vulva, that is of the external part of the female genitals.

Infections, allergic reactions and traumatic injuries are among the predisposing and triggering factors of the vulvitis. Furthermore, the mucosa and skin of the vulva are particularly vulnerable to irritation due to local humidity and heat.

The vulvitis symptomatology is essentially represented by redness, itching, edema, burning and tenderness. Vulvar irritation can be aggravated with sexual intercourse and the habit of excessive intimate hygiene. Furthermore, vulvitis can coexist with vaginitis of various kinds (inflammation of the vagina); in this case we speak of vulvovaginitis .

Inflammation is diagnosed by physical examination and identification of any microorganisms responsible for the altered physiology of the vulvo-vaginal environment.

Treatment is directed to the triggering cause, elimination of irritating factors and correction of hygiene habits.

Outline of anatomy: what is the vulva?

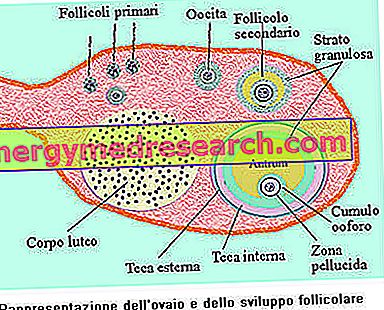

From the anatomical point of view, the vulva is the region that surrounds access to the vagina and coincides with the female external genitalia .

More precisely, this organ includes the following structures:

- Pubic mount : relief of skin and underlying adipose tissue located centrally in the pelvic region.

- Big and small lips : group of outer and inner folds surrounding the outer opening of the vagina.

- Vaginal vestibule : area enclosed by small lips that leads to the meatus of the vagina and urethra.

- Clitoris : small erectile organ located in front of the vestibule.

- Bartholin's glands : a pair of small glands that secrete a lubricating fluid that facilitates penetration of the penis into the vagina during sexual intercourse.

The hymen and the external orifice of the urethra are also found in the vulvar complex.

Who is at risk?

Vulvitis can affect women of any age, although girls who have not yet reached puberty and older women may be more likely to develop the disorder.

After menopause, in particular, a marked decrease in estrogen causes a progressive thinning of vulvar and vaginal mucous membranes; this phenomenon can accentuate the characteristics of some inflammatory processes.

Causes

Vulvitis can be determined by numerous causes:

- Fungal infections (eg Candida albicans ), bacteria (eg streptococci, staphylococci and enterococci), protozoa (such as Trichomonas vaginalis ) and viruses (such as herpes simplex);

- Parasitosis, including scabies or pediculosis of the pubis;

- Sexually transmitted diseases, including gonorrhea, trichomoniasis and chlamydia;

- Scratch- induced micro-trauma due to local itching, abrasions due to inadequate lubrication during sexual intercourse and rubbing against too tight clothing;

- Prolonged contact with a foreign body, such as a condom, internal sanitary napkins, residues of toilet paper or grains of sand;

- Hormonal alterations (note: the decrease in estrogen levels predisposes to dryness of the mucous membranes and reduces their thickness, making the vulvar tissues more vulnerable to irritation);

- Allergic reactions to detergents used for hygiene of the genital area, intimate deodorants and depilatory creams, vaginal lubricants, latex condoms, spermicides and residues of laundry detergents;

- Dermatological disorders (including seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, psoriasis, irritative dermatoses, etc.) and vulvar dystrophies, such as genital lichen sclerosus or squamous cellular hyperplasia.

Other factors that can promote inflammation of the vulva include:

- Injuries due to sexual trauma;

- Chemical irritation from urine or faeces in incontinent or bedridden patients;

- Poor intimate hygiene and poor behavioral habits, such as wiping from back to front after evacuation and not washing hands after defecating;

- Abuse of topical substances (vaginal lavages, deodorant sprays, depilatory creams, aggressive detergents and perfumed toilet paper);

- Use of non-breathable sanitary pads or panty liners, underwear made with synthetic fabrics (such as nylon and lycra) and over-tight clothes that cause skin friction (body, leggings, tights and jeans) for long periods of time;

- Drug therapies based on antibiotics or corticosteroids.

In addition, vulvitis can be associated with psychosomatic disorders, unbalanced diets (including situations of avitaminosis and malnutrition), urinary incontinence and obesity. Other predisposing factors include imbalances associated with states of immunodepression and systemic diseases, such as diabetes and uremia.

Vulvitis in children

During childhood and adolescence, inflammation of the vulva is mainly determined by allergic reactions, irritative contact dermatitis, lichen sclerosus and infectious processes.

In newborns, dermatitis of the vulva is generally caused by failure to replace a dirty diaper for an extended period of time; in most cases, increasing the frequency of the change and applying topical emollients are sufficient measures to solve the problem.

In older children, however, dermatitis is mainly due to exposure to an irritant, represented, for example, by soap and laundry detergent; in this case, the vulvitis can be prevented by correcting the hygiene habits and the suspension of the use of the sensitizing substance. Other treatment options for vulvar dermatitis include the oral intake of hydroxyzine hydrochloride or topical application of hydrocortisone.

In childhood, the organisms responsible for infectious vulvitis include pinworms ( Enterobius vermicularis ), Candida albicans and group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus. These infections occur mainly after antibiotic therapy and in children with diabetes or immunosuppressed.

Lichen sclerosus is another common cause of vulvitis in children. The disorder appears in the skin region around the anus and the vulva, causing skin fissures, hypopigmentation, skin atrophy, plaques, excoriation, dysuria and itching. In severe cases, dark purple bruises (ecchymoses) may appear on the vulva, blood loss and scarring. The cause is unknown, but probably genetic or autoimmune factors participate in the etiology. If the skin changes are not evident at the visual check, the doctor can perform a skin biopsy to get an exact diagnosis. Treatment for lichen sclerosus involves the use of topical corticosteroids.

Symptoms

Depending on the causes, vulvar inflammation can occur with very variable characters.

Generally, the vulvitis shows:

- Intense and persistent vulvar itching;

- Redness of the small and large lips;

- Edema and tenderness of the vulva.

In some cases, there may also be excoriations, fissures, a burning sensation, small suppurating blisters and ulcerations. At other times, the vulva may be covered with thickened painful, scaly and whitish patches.

Local irritation can also involve secretions or mild bleeding, burning pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia) and dysuria (pain on urination). Often, there is a simultaneous involvement of the vagina (vulvovaginitis).

Possible consequences

In incontinent or bedridden patients, poor hygiene can lead to chronic vulvitis due to prolonged contact with urine or feces.

If they are not treated properly, vulvitis can be complicated by infections that can develop into vaginitis, urethritis and cystitis . Rarely, the chronic inflammatory process can create labial adhesions, that is adhesions at the level of the folds around the vaginal and urethral orifice.

Diagnosis

The vulvitis is diagnosed based on the symptoms and signs that emerged during the collection of anamnestic data (complete medical history of the patient) and the gynecological examination. The pelvic exam shows redness, changes in the skin, vulvar edema and lesions that can indicate the presence of inflammation.

Upon inspection, the doctor may also find possible excoriations, fissures and vesicles, as well as checking for vaginal discharge. Such secretions can be subjected to analysis to define whether the vulvitis depends on an infection; the microscopic examination of this material, in fact, provides a first indication of the etiology of the vulvitis. If the results of examinations in the clinic are inconclusive, the secretion can be cultured.

A symptomatology associated with particular hygienic or behavioral habits can indicate a vulvitis triggered by irritating factors.

The doctor may also use a swab to take a sample of secretions from the cervix to check for sexually transmitted infections and collect a urine sample to rule out more serious causes of vulvar irritation.

Treatment

The treatment addresses the causes of vulvitis:

- In the case of a bacterial infection, the therapy involves the use of antibiotics, to be taken orally or topically applied, for a few days.

- In the presence of fungal infections, however, the use of antifungal drugs is indicated.

- When irritative reactions are found, however, it is necessary to avoid the sensitizing agent (when recognized).

- If the symptoms are moderate or intense, the doctor may prescribe a pharmacological treatment based on antiseptic and anti-inflammatory products, such as benzidamine. To relieve the itchy sensation, the application of topical corticosteroids may be indicated.

In addition to scrupulously following the therapy indicated by the gynecologist, the management of the vulvitis must include the correction of hygienic habits:

- Keep the vulva clean and dry, changing underwear frequently and taking care of daily personal hygiene;

- After each evacuation, remember to dry the skin and mucous membranes carefully from the front to the back and always wash your hands.

- Until a successful recovery, it is advisable to abstain from sexual intercourse or to use a condom.

- Prefer cotton clothing, a fabric that reduces local humidity and ensures proper tissue transpiration, as well as limiting the stagnation of secretions and the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms.

If chronic vulvitis does not respond to treatment, doctors usually proceed with a biopsy to rule out the presence of skin disorders (vulvar dystrophies, such as lichen sclerosus or squamous cell hyperplasia) or cancer of the vulva.

Prevention

- Daily and post-coital intimate hygiene must be accurate, but not excessive, as it could alter the natural immune defenses of the external genitals;

- Do not use detergents for intimate hygiene that are too alkaline or rich in dyes;

- Avoid applying spray deodorants, perfumed intimate wipes and depilatory creams on the vulva;

- Limit the use of occlusive and antiperspirant panty liners, inner pads and synthetic underwear to prevent vulvar and vaginal environmental changes;

- Respect the food standards for a correct and balanced diet.